Place of Birth: Sandy Cove [now Dort's Cove], Guysborough County

Mother's Name: Isabelle Maude Crane (1869-1946)

Father's Name: Freeman Whitfield Horton (1860-1938)

Date of Enlistment: April 12, 1915*

Regimental Number: OFF VR-426

Rank: Skipper

Force: Royal Naval Canadian Volunteer Reserve

Location of service: Halifax & Sydney, NS

Occupation at Enlistment: Mariner

Marital Status at Enlistment: Single**

Next of Kin: Mrs. Gwladys Mary (Jenkins) Horton (wife), 32 1/2 S. Clifton St., Halifax, NS**

*: Official date of enlistment as recorded in Royal Canadian Navy personnel file. Isaiah began service with the RCN on February 4, 1915.

**: According to family sources, Ike and Gwladys were married in June 1915, shortly after his enlistment.

*****

|

| Skipper Isaiah Walton 'Ike' Horton |

Isaiah Walton 'Ike' Horton was one of such individual, the oldest son and third of six children born to Freeman Whitfield and Isabelle Maude (Crane) Horton of Guysborough, Nova Scotia. Ike's family traced its Nova Scotia roots to his namesake, who was one of Guysborough's 'Nine Old Settlers'. It is not surprising that Ike pursued both a civilian and military career at sea. His father was a master mariner who also served as an officer with the RNCVR during the war, and all of his paternal uncles earned a living on the water.

|

| Ike with sisters Gertie and Hilda (l to r), parents Isabelle and Freeman Horton. |

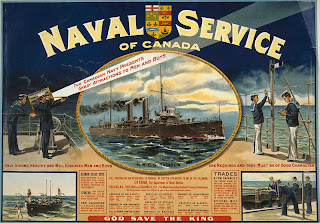

In the years prior to World War I, the RCN's lack of resources meant that Royal Navy ships and Department of Marine & Fisheries' 'Dominion Cruisers' such as the Constance provided most of Canada's coastal protection. In fact, the first Director of the Naval Service of Canada - later re-named the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) - was the Marine & Fisheries Department's former head, Rear Admiral Charles Kingsmill.

Ike had served in the Canadian coastal defence service for more than a year when Britain declared war on Germany on August 4, 1914. The RCN immediately assumed responsibility for the Department of Marine & Fisheries' operation, as its vessels formed the nucleus of its coastal defence resources. The Constance was absorbed into the naval service and assigned to patrol and 'examination' duties on Canada's Atlantic coast.

|

| HMCS Constance |

On June 25, 1915, Ike was officially promoted to Mate, serving with HMCS Canada for two months. A former CGS vessel that conducted patrols as part of the Fisheries Protection Service, HMCS Canada is considered the nucleus of the modern-day RCN due to its central role in training naval officers and asserting Canadian sovereignty. Commissioned into service for the war and refitted as a naval patrol vessel, its forecastle was raised and four guns - two 12-pounders and two 3-pounders - were mounted to its decks. HMCS Canada was anchored in Halifax Harbour on December 6, 1917, sustaining only minor damage and one slight casualty in the famous explosion. Decommissioned in 1919, it returned to service as CGS Canada before being retired in 1920.

|

| Crew of HMCS Canada (Ike Horton not identified in photo). |

|

| HMCS Hochelega |

|

| Crew of HMCS Sable Island (Ike Horton above the letter 'E'). |

Ike's service record contains several letters written during his time in Halifax, relating to two matters discussed at length with his superiors. In a letter dated August 20, 1916, Ike stated that he had served 18 months as Mate with the RNCVR at a pay rate of $ 2.50 per day. As he had been in charge of several patrol vessels during this time, he requested an increase to 'Command Money'. Navy Headquarters initially denied his request, noting that his navy pay was considerably more than his $ 45.00 monthly salary as a Fisheries Protection Officer.

A second letter dated February 9, 1917 again requested payment of 'Command Money', noting that Ike had served as commander of HMCS Starling for nine months and HMCS Premier for three months. Upon reconsideration, Naval Headquarters approved a raise in salary to 'Command Money' effective December 19, 1916.

|

| Ike's father Freeman Whitfield Horton (left) & unidentified crew. |

Once again, Naval Headquarters in Ottawa initially rejected Ike's request, stating that while his service was "well known", at this point in his career Ike lacked "the necessary experience and cannot be offered appt. [sic] at present while there are so many older men with years more experience." Meanwhile, on January 17, 1918, Ike was appointed Mate of the tugboat Gwennith, operating out of Halifax Harbour. Almost exactly one month later - on February 18, 1918 - he was promoted to the rank of Skipper.

|

| Skipper Isaiah Walton Horton (left) with father, Freeman Whitfield Horton. |

In response, the RCN rented facilities on the Sydney waterfront and established Lansdowne base early in 1918. By year's end, almost 100 RCN coastal patrol vessels, 1500 crew and shore personnel operated out of Sydney, patrolling the Cabot Strait and Gulf of St. Lawrence. A "Mobile Patrol Flotilla" consisting of several divisions, each outfitted with one or two former CGS vessels and a pair of trawlers, patrolled the Gulf of St. Lawrence and waters along the Newfoundland coast ready to respond to reports of German submarine sightings and assist convoys as they departed Halifax and Sydney.

The remainder of the RCN trawlers and 'drifters' located at Sydney were assigned to the "Forming Up Escort & Outer Patrol Flotilla" and tasked with acting as a screen protecting 'HS' (slow-moving) convoys as they left Sydney and formed up in the Cabot Strait prior to crossing the Atlantic. The first convoy departed from Sydney in early July 1918, escorted by three United States submarine chasers, vessels considerably faster than any RCN craft.

Meanwhile, Ike and the Gwennith operated out of Sydney, hauling a small supply barge capable of navigating tiny coves to various locations on the Newfoundland and Labrador coastline. Robert H. Worthen, a Captain with whom Ike worked in this area, described him as having "a studious, rather locked-in face, which belied his real self. He was as riotous as sea captains of myth." According to the Captain's memoirs, throughout the last months of the war, Worthen and Ike sailed along the Newfoundland and Labrador coast while their wives passed the time in Sydney pursuing a fascination for fortune-telling. Worthen recalled at least one occasion on which Ike guided their vessels to safety into a tiny cove after sighting a German submarine.

|

| Skipper Isaiah Walton Horton (back row, 3rd from right) with unidentified crew. |

A government notice the following year provided the opportunity for funds to finance such an endeavour. It was a long-standing Royal Navy tradition to pay 'prize money' to ships' officers and crews for capturing or sinking enemy vessels in wartime. A similar reward was provided for saving or salvaging ships and cargo.

On October 4, 1920, Ike wrote to the Department of Naval Service, claiming his share of "prize money". He cited his service as "watch keeping officer" on the vessels Canada, Sable Island and Hochelega as well as his role as mate and commander of Sterling and Premier before his promotion to Skipper, adding that "about all my time was on patrol duty". While there is no record of the sum received, in later years his daughter Gertrude recalled that Ike used the funds to purchase the Westport III, one of two ships with which Ike established a coastal freight and passenger business.

|

| Coastal steamer Westport. |

Ike's second purchase was the SS Elaine, initially built as a coastal defence (CD) boat in Montreal in 1917. Slightly smaller than the Westport - 84 feet in length in comparison to the Westport's 101 feet - it was the namesake for Ike's first post-war business venture. The Elaine Steamship Company initially operated at 32 Hollis St., Halifax and Guysborough before focusing exclusively on passenger and freight traffic in the Strait of Canso. Ike refitted the Westport with two Fairbanks, Morse & Co. gas-powered engines after securing the contract to move freight and passengers between the towns of Mulgrave and Canso.

On its operating days, the Westport travelled from Canso to Mulgrave, arriving prior to 11:30 am, the departure time for Canadian National's train to Truro. The vessel remained dockside until the afternoon train arrived at 2:30 pm, at which time it made its return run, stopping at Queensport en route. As owner and Captain, Ike maintained this service throughout the 1920s, eventually selling the Company and Westport III to the Eastern Canadian Steamship Co., a Saint John business that gradually purchased and operated virtually all Maritime coastal shipping routes. The Westport continued to operate along the Strait of Canso until March 1934, when it ran aground near Oyster Ponds/Hadleyville and was crushed in sea ice during a spring storm. All on board safely reached shore, but the vessel was damaged beyond repair.

|

| Ike (right) with siblings Aubrey, Hilda and Maud (left to right) in later years. |

In 1936, Ike relocated his family to Halifax, where he established "Horton & Co. Ltd., Ship Brokers". The Company sold marine engines and supplies in addition to buying and selling ships in the Atlantic region and beyond. A March 1958 letter to Ike from Commercial & Shipping Agency, Kingston, Jamaica inquiring about "a list and particulars of small ships which you have for sale" indicates that his clientele extended as far as the Caribbean Islands. A second letter from the Jamaican Ministry of Trade, dated November 28, 1960, provided addresses for two Jamaican shipping brokerages, suggesting that Ike's company was actively pursuing business on the small island.

|

| Letterhead of Horton & Company Ltd. |

Isaiah Walton Horton passed away at Camp Hill Hospital, Halifax on August 17, 1979. Pre-deceased by his wife Gwladys, who died in 1969, Ike returned home to Guysborough, where he was laid to rest in Evergreen Cemetery beside his beloved wife.

|

| Gravestone of Gwladys & Isaiah Horton, Evergreen Cemetery, Guysborough, NS. |

*****

Sources:Cook, Christopher A.. Along the Streets of Guysborough, 2nd Edition. Antigonish, NS: The Casket Printing & Publishing Co., Ltd., 2003.

RCN Ledger Sheet for I. W. Horton, OFF VR-426. Library & Archives Canada, Ottawa: RG 150, 1992-93/170, Volume 27.

RCN Service Record of I. W. Horton, OFF VR-426. Library & Archives Canada, Ottawa: RG 24, 1992-93/169, Box 100. Copy provided by Mrs. Maureen Horton Taylor, Spruce Head, Maine.

Tennyson, Brian & Sarty, Roger. "Sydney, Nova Scotia and the U-Boat War, 1918". Canadian Military History, Volume 7, Number 1, Winter 1998, pp. 29-41. PDF copy available online.

A special thank you to Maureen Horton Taylor, Spruce Head, Maine, who provided valuable information on Ike's life accumulated from a variety of sources, in addition to the family photographs displayed in this post.