Place of Birth: Cook's Cove, Guysborough County

Mother's Name: Esther Ann "Annie" MacDonald

Father's Name: John Henry Cook

Date of Enlistment: January 24, 1916 at Windsor, NS

Regimental Number: 733899

Rank: 2nd Lieutenant

Forces: Canadian Expeditionary Force (Infantry); Canadian Army Medical Corps (CAMC); Royal Flying Corps (RFC)

Units: 112th Overseas Battalion; No. 9 Stationary Hospital, CAMC; No. 53 Squadron, RFC

Location of service: England and France

Occupation at Enlistment: Student

Marital Status at Enlistment: Single

Next of Kin: John H. Cook, Guysborough, NS (father)

*****

Clarence William Cook was the second of three children born to John Henry and Esther Ann "Annie" (MacDonald) Cook of Cook's Cove, Guysborough County. His mother, Annie, passed away sometime after 1901, and John Henry subsequently married Sarah Jane (Stearns) Carr. Clarence's stepbrother, Albert Henry — John Henry and Jane's only child — was born in 1903.

The elder of the John Henry and Esther's two sons, Clarence completed his grammar school studies at Guysboro Academy and enrolled in the Bachelor of Arts program at Acadia University, Wolfville. Sometime after the outbreak of war in Europe, he joined the 81st "Hants" Regiment, an eight-company militia unit organized at Windsor, NS in February 1914.

|

| Clarence William Cook (Acadia University graduation photograph). |

*****

The 112th (Nova Scotia) Battalion was authorized on December 22, 1915 and mobilized at Windsor, NS. A significant number of its early recruits came from the 81st Hants militia regiment. After several months' training, its personnel travelled to Halifax, boarding SS Olympic for the trans-Atlantic voyage. Upon arriving in England eight days later, the unit made its way to camp in southern England.

Clarence was promoted to the rank of "Acting L/Col." [Lance Corporal] on the same day the 112th arrived in England, but reverted to the rank of Private "at [his] own request" on August 29, 1916. Throughout the autumn of 1916, his battalion provided reinforcements for CEF units in the field, its remaining personnel absorbed by the 26th Reserve Battalion on January 7, 1917.

By that time, Clarence's military career had taken another direction. On December 19, 1916, he was transferred to No. 9 Stationary Hospital, CAMC, Bramshott, and commenced service as a hospital orderly. Authorized on February 1, 1916 under the sponsorship of St. Francis Xavier University, Antigonish, NS, No. 9 Stationary had arrived in England on June 29, 1916 and three months later assumed operation of Bramshott Military Hospital, catering to the medical needs of Canadian soldiers stationed at Bramshott and Witley military camps.

During the winter of 1916-17, the hospital's resources were stretched to the limit by a severe influenza outbreak in the Bramshott area. Clarence also experienced health problems shortly after joining the unit. He was admitted to Bramshott on February 12, 1917, suffering from a sore throat, general aching, headache and chills. His temperature spiraled to 103 degrees Fahrenheit (39.4 Celsius) and his pulse was 90 at the time of admission.

After examination and medical tests, Clarence was diagnosed with diphtheria and transferred to Military Isolation Hospital, Aldershot the following day. He spent four weeks recovering and was discharged on March 13, only to be readmitted on April 5 for additional treatment. Finally, on May 1, medical personnel determined that he had made a "complete recovery" and discharged him to duty.

Clarence returned to No. 9 Stationary, serving with the unit into the summer months. As with many young men stationed in England, he longed to see action at the front. His university education proved to be an asset, earning admission to the Royal Flying Corps' cadet training program. On August 1, 1917, Clarence reported to Cadet Wing, RFC, Thurston Park, Winchester, where he commenced the second phase of his military career.

*****

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was established by royal warrant on April 13, 1912. Its inaugural staff consisted of 133 Officers, operating 12 manned balloons and 36 aircraft. By November 1914, the RFC had expanded sufficiently to justify the creation of "wings" consisting of two or more squadrons, each under the command of a Lieutenant-Colonel.

Further expansion in subsequent years led to the establishment of Brigades in October 1915 and specific Divisions, including a Training Division established in August 1917. Throughout the latter year, British military authorities dramatically expanded the country's air resources, in an effort to overcome the German Air Force's domination of the skies during the conflict's early stages.

The recruitment and training of Canadian soldiers as pilots was an integral part of this plan. Clarence was amongst a group of cadets who reported to the RFC's Military School of Aeronautics at Reading, England on August 24, 1917. Five days later, he was officially "discharged from the Canadian Expeditionary Force, "having been appointed to Commission in [the] Imperial Army — RFC — 30/8/17." Documents at the time described his military character as "Very Good".

Upon completing his training, 2nd Lieutenant Clarence William Cook was assigned to No. 53 Squadron, RFC as a "Flying Officer (Observer)" and crossed the English Channel to France on October 2, 1917.

Established as a training squadron on May 15, 1916, No. 53 initially operated at Catterick, North Yorkshire, England. The location's airfield first opened in 1914 and became a base for pilot training and aerial defense of England's northeast coast after the outbreak of war in Europe.

No. 53 Squadron proceeded overseas to France in December 1916, its pilots initially flying the British-manufactured B. E. 2 (Blériot Experimental) airplane. Powered by a single engine, the two-seat biplane was used for front-line reconnaissance and light bombing, as well as "night fighter" missions. By late 1917, however, the Squadron returned to its initial plane, the Royal Aircraft Factory's R. E. 8 (Reconnaissance Experimental).

|

| Royal Aircraft Factory's R. E. 8 |

The pilot operated the camera on reconnaissance flights and used a Morse key for communication when directing artillery fire. Meanwhile, the observer — Clarence's role —scanned the skies for approaching enemy aircraft. The RFC's most popular two-seater plane, Royal Aircraft produced more than 4000 R. E. 8 aircraft during the war years, making it one of the most common sights in the skies above the Western Front.

In November 1917, No. 53 Squadron was located in the vicinity of Balleuil, France, close to the Belgian border. Its pilots operated its R. E. 8 fleet as part of RFC's Ninth Wing, flying in conjunction with No. 19 Squadron's single-pilot fighter aircraft — French-manufactured Spads and their eventual replacement, the newly introduced Sopwith Dolphin.

Clarence's arrival in France coincided with a major offensive operation, carefully planned by British commanders during October 1917 and organized around the use of another new weapon of war — the tank. Unlike previous attacks during the summer-long Somme campaign, there would be no preliminary bombardment. Instead, the "land ships", as they were initially named, would cut a path through the German wire and crush opposing machine gun emplacements as infantry units advanced in their wake.

The attack was to be launched along a six-mile front at Cambrai, France. Air support would play a critical role, with Ninth Wing's squadrons instructed to conduct bombing and reconnaissance missions alongside fighter and bomber aircraft of I and III Brigades. Ninth Wing's pilots were assigned specific bombing targets, in addition to the task of observing troop movements in the area of the Sensée River, east of Cambrai, and southward toward the village of Masnières.

British forces commenced the advance at precisely 6:00 a.m. November 20, 1917. Thick mist and low cloud made flying difficult but assisted the advancing tanks and infantry. While fighter and bomber aircraft attacked German airfields and artillery positions, R. E. 8 observer aircraft from Clarence's and other RFC squadrons focused on locating active German batteries and bodies of troops, in addition to identifying guns being deployed against the advancing tanks.

The morning mist made the task of locating German artillery almost impossible, unless an aircraft was in the immediate area when the guns fired. Contact patrol observers reported on the advancing infantry's progress, but failed to note significant German resistance in the village of Fontaine-Notre-Dame, to the east of Bourlon Wood. The fog and cloud cover also hampered the planned bombing raids.

The attack continued throughout the following two days, focusing on well-fortified enemy positions at Bourlon Wood, a strategic ridge overlooking German defenses south of the Scarpe and Sensée Rivers. Advancing units succeeded in securing the area on November 23, but were unable to dislodge German forces from nearby Fontaine-Notre-Dame.

That same day, German aircraft received much-needed reinforcement, as Baron Manfred von Richthofen's "Flying Circus" hastily arrived from nearby Flanders. From this point forward, von Richthofen assumed command of all fighting units deployed at Cambrai. The sight of his squadron's colorful aircraft in the skies above the battlefield was an ominous reminder of their presence throughout the battle's remaining days.

As the British advance slowly ground to a halt and focused on consolidating its gains, German forces began preparations for a counter-attack. While RFC aircraft reported considerable evidence of troops and resources concentrated behind the line at Bourlon Wood, German commanders quietly planned an attack at a much more vulnerable section, near the village of Masnières.

German forces launched the counter-attack in the early hours of November 30. As with the initial British attack, mist severely hampered visibility from the air. At times, more than 50 RFC planes flew over the front lines in a desperate attempt to observe enemy movement. Continuous aerial combat with opposing German planes also hampered the RFC's ability to assist troops on the ground.

The German counter-attack succeeded in forcing British units to retreat and threatened to cut off the soldiers occupying Bourlon Wood. As a result, British commanders ordered a gradual withdrawal from the location, completely relinquishing the captured position by the morning of December 7 as both sides returned to their pre-battle lines.

The Battle of Cambrai (1917), as it came to be known, held several important lessons for aerial combat. German aircraft exercised low-lying attacks on British infantry units during the counter-attack, with considerable success. However, the daily "casualty rate" from such action in terms of aircraft lost was considerable — approximately 30% — rendering such tactics catastrophic in a prolonged battle.

Cambrai also highlighted the importance of accurate air observation, particularly the need for sufficient visibility to guide the infantry's advance and identify enemy artillery positions and bombing targets. Such lessons would not be forgotten in the conflict's final year.

In the aftermath of the battle, both sides settled into the pattern of the war's previous three winters. Military activity in the trenches declined considerably as both sides coped with winter conditions. Aerial forces experienced a similar decline, weather hindering effective observation, particularly throughout the month of January 1918.

RFC observation flights nevertheless indicated significant concentrations of German forces along the front lines near Amiens, France, leading to speculation of an upcoming offensive. Throughout February 1918, observers reported increased train movement, newly constructed ammunition dumps, aerodromes and gun emplacements, further suggesting that the German military was preparing for an attack.

Later that same month, No. 53 Squadron relocated to Villeselve, northeast of Noyon, France, in preparation for the transfer of a French section of the line near Soissons to British forces. The events of March 1918, however, brought dramatic changes of plans for both Clarence and the squadron.

On March 3, 1918, the new Bolshevik government of Russia signed a peace treaty with Germany, ending combat along their common border. Having struggled for three and a half years to wage war on two fronts, Germany was finally able to concentrate exclusively on the Western Front. The German High Command immediately commenced relocating its personnel and weapons, setting in motion an elaborate plan for a major Spring Offensive.

Its timing was crucial, as British and French forces anticipated the arrival of American troops along the Western Front in the upcoming months. If Germany could register a major success — perhaps a successful push to the Channel coast, or even the capture of Paris — the war might end before the United States had fully deployed its resources in Europe.

Throughout the month of March, the RFC focused on gathering information on an impending offensive, venturing as far as nine miles behind German lines. Air patrols were particularly frequent along a section of the line occupied by the British 3rd and 5th Armies, the location where Allied Commanders expected the attack to occur.

On March 7, Ninth Wing's squadrons moved south to the 5th Army Sector, an area stretching from Cambrai to Le Catalet — by coincidence, the centre of the eventual German offensive. While primarily assigned to observation missions, No. 53 Squadron's R. E. 8s also dropped bombs while engaging in artillery co-operation and close reconnaissance, and carried out night bombing raids.

Air reconnaissance quickly revealed German forces marshaling both men and material in preparation for a ground assault. Unfortunately, rain and thick clouds from March 17 to 20 rendered observation almost impossible. By this time, however, information from captured German airmen and soldiers suggested a specific date for the attack — March 21, 1918.

On the eve of battle, both sides had assembled considerable aerial resources. The Royal Flying Corps had a total of 579 planes available, 261 of which were single-seat fighters. Their German opponents possessed 730 aircraft, 326 of which were fighter planes. In this particular instance, German air power significantly surpassed their British opponents.

At 4:45 a.m. March 21, German artillery launched massive artillery barrages at several separate locations along the Western Front, stretching from Belgium to central France. The tactic was designed to disguise the assault's actual location until the last moment. Before daybreak, German infantry units advanced toward a sector held by part of the 3rd and the entire 5th British Armies, stretching from the Sensée to the Oise River in France. Operation Michael — the German army's massive Spring Offensive — had begun.

As was the case at Cambrai, mist assisted the offensive, inhibiting visibility on the ground and in the air. As the fog lifted around 1:00 p.m., RFC planes took to the air to assess the offensive's progress, quickly identifying large concentrations of German troops south of Cambrai. No. 53 Squadron's planes conducted line patrols along the entire 5th Army front from 1:20 p.m. onward, dropping bombs and firing their machine guns on advancing German troops until darkness prevented further flights.

A dense fog once again hung in the air from dawn until mid-day March 22, rendering aerial observation almost impossible. During the afternoon, No. 53 Squadron resumed its low-flying attacks on advancing German infantry units, using 25-pound bombs and machine guns to deter their progress. Its observers also attempted to protect the Corps' planes from attack, carefully scanning the skies for enemy aircraft.

The day's aerial reconnaissance reported widespread activity behind the German line, further evidence that the 5th Army's front was the focal point of attack. On March 23 — the third day of fighting — an early morning haze quickly lifted, providing pilots with excellent visibility. As a result, more aerial combat occurred on this day than on the previous two days combined.

By nightfall, RFC pilots had destroyed 39 German aircraft along the entire British front, although at considerable cost. A total of five RFC planes were "missing", 28 "wrecked from all causes" and five "burnt or abandoned". Lieutenant Clarence William Cook's R. E. 8 was amongst the five "missing" aircraft.

The German Spring Offensive continued for two weeks before grinding to a halt at Amiens, France on April 5, 1918. While German forces advanced 65 kilometres into British-held territory, the action failed to achieve its primary objective — reaching the English Channel and establishing a wedge between the British and French armies on the Western Front. In sum, Operation Michael failed to achieve the decisive victory required to bring the war to an end.

The offensive had a dramatically different impact on Clarence Cook's war experience. He was taken prisoner after his plane crashed behind German lines on March 23, 1918. Clarence hurt his shoulder in the crash — an injury from which he never fully recovered — but was otherwise in good health as his captives transported him to a German prisoner of war camp for the final phase of his military experience.

*****

Amongst the almost 418,952 Canadians who served overseas (i.e., in England, France or Belgium) during the First World War, a total of 3,847 Canadian soldiers — 132 Officers and 3,715 "other ranks" (OR), representing less than 1% of infantry personnel — became prisoners of war. An astonishing 1,400 were captured in one battle — the poison gas attack launched on Canadian troops during the 2nd Battle of Ypres (April 1915). Approximately 182,000 British soldiers suffered a similar fate, representing approximately 4% of the almost five million men who served during the conflict.

The small number of infantry POWs can be attributed in part to their units' emphasis on soldiers fighting to the end and refusing to surrender. In fact, after the war, many battalions proudly proclaimed that none of its soldiers were taken prisoner during the war.

|

| Clarence's POW card. |

Once taken prisoner, soldiers and airmen were theoretically protected by the terms of the Geneva Conventions of 1864 and 1906, international agreements intended to guarantee the humane treatment of soldiers no longer participating in hostilities — the wounded, sick and prisoners of war. The realities of POW camps, however, differed considerably from the ideals stated in both documents, as poor living conditions, systematic lack of nutrition and harsh treatment occurred on both sides of the conflict.

German authorities divided prisoners of war into two categories. "Other ranks" were interned at a "Mannschaftslager", a basic camp consisting of wooden barracks ten meters wide and 50 meters long, covered on the outside with tar paper. Each barrack held 250 POWs and contained a central corridor that provided access on each side to two-tiered straw or sawdust beds. The barrack was furnished with a few tables, chairs or benches and a stove.

The camp also contained a guard's barracks, a canteen that sold small food items, and a guardhouse. Rank and file POWs labored in nearby workshops or on farms, receiving pay in the form of "Notgeld" — camp currency usable only at the POW camp store — as compensation.

A barbed wire fence three meters in height defined the camp's perimeter. Wooden posts, erected at three-meter intervals, supported a 50 centimeter grid of horizontal and vertical wiring, creating a virtually impenetrable barrier.

Officers were usually held in an "Offizierlager", where conditions were less harsh. The camps were often located in existing buildings requisitioned for such a purpose — often castles or hotels — and provided more spacious accommodations and beds. Unlike their OR counterparts, Officers were not required to work, passing the time in various recreational or educational pursuits.

As the war progressed, conditions in the German camps worsened, particularly during the final year when food shortages hampered their captors' ability to provide sufficient nutrition. Commonwealth POWs often fared better than soldiers from other Allied nations, as many received regular parcels from home during their detention.

|

| Sentry at gate, Niederzwehren POW Camp. |

The camp became home to large numbers of POWs captured during the German Spring Offensive. Throughout their time in detention, the men endured heavy workloads and suffered from malnutrition. Unfortunately, Clarence's "POW Card" contains little information other than his name and rank, and there is no other record of his time at Niederzwehren.

The timing of Clarence's internment proved somewhat fortuitous, as Allied forces launched a successful counter-offensive in August 1918 and succeeded in bringing hostilities to an end three months later. The terms of the November 11, 1918 Armistice that ended the fighting specifically required the immediate release of all French, Commonwealth and Italian POWs, delaying the release of their German counterparts until a formal peace treaty was signed.

Despite the use of the word "immediate", several weeks passed before POWs detained in German camps were released. Clarence's RFC service record indicates that he was "repatriated" on December 26, 1918. He subsequently made his way to England, departing for Canada on January 30, 1919. Three months later — April 30, 1919 — Lieutenant Clarence Cook was formally discharged from military service.

|

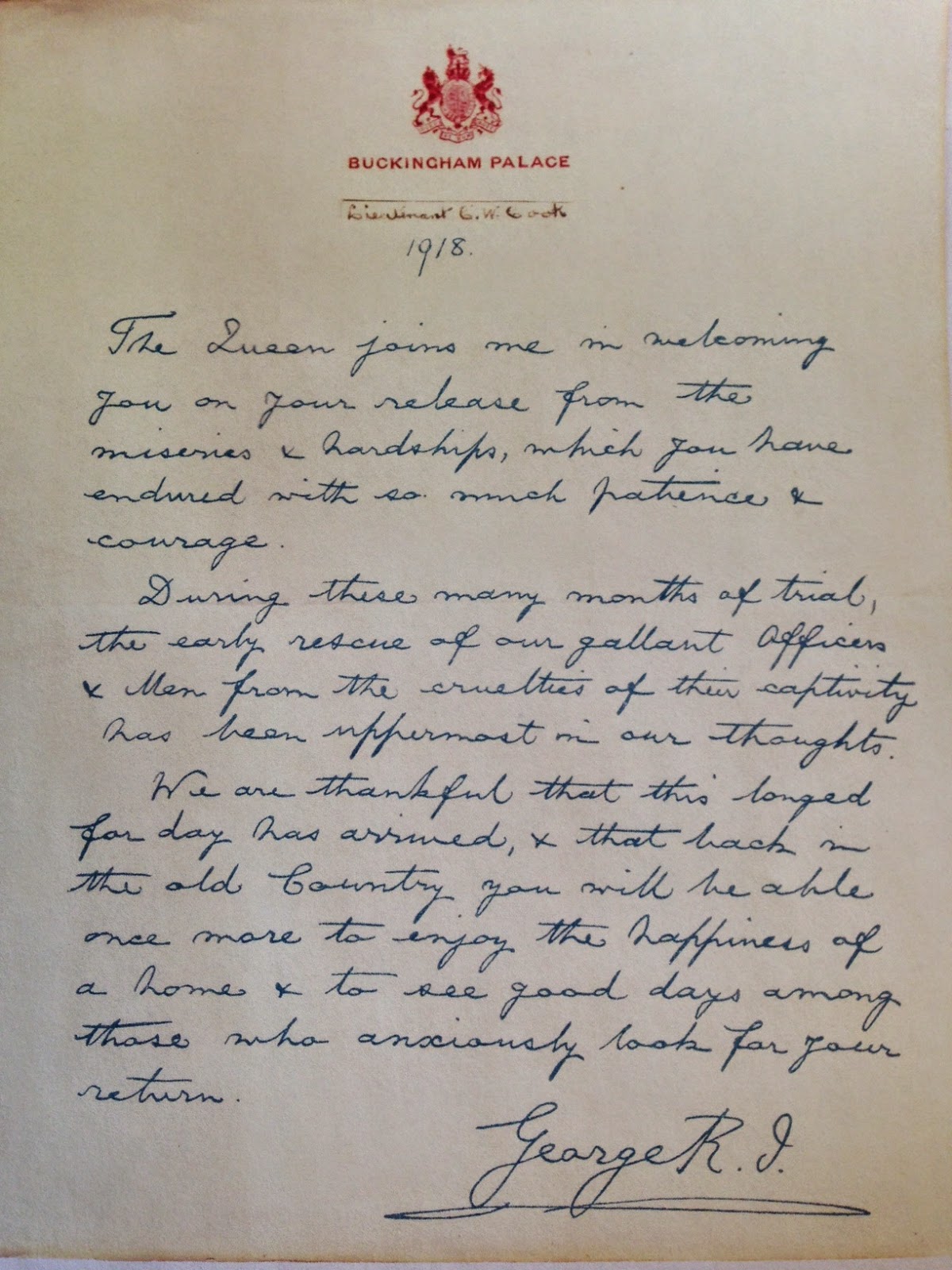

| King George V's letter to Commonwealth POWs. |

*****

Several post-war events suggest that Clarence quickly settled into civilian life. On June 18, 1919, he married Gladys Henrietta Eaton, a native of Granville Centre, Annapolis County. The ceremony took place in Gladys' hometown, after which the newlyweds settled in Parrsboro, where Clarence commenced service as a Baptist minister.

After three years in the small Minas Basin community, Clarence decided to return to school, completing studies for a Bachelor of Divinity degree at Newton Theological Seminary, Massachusetts from 1922 to 1924. During their time in the United States, Gladys gave birth to the couple's only child, Murray Eaton Cook.

Following graduation, Clarence returned to Nova Scotia, tending to the spiritual needs of Maritime congregations for more than three decades. He served the first three years at Milton, Queens County (1924-27), followed by eight years in Canning (1927-35) and five years in Kingston, NS (1935-40).

During the 1940s, Clarence and his family relocated to Summerside, PEI (1940-44) and Quebec City, PQ (1944-48), subsequently returning to Nova Scotian congregations at Berwick (1948-55) and Chester (1955-60). After 36 years in ministry, Clarence retired to Canning, NS, where he was appointed Honorary Pastor of the community's United Baptist Church.

His obituary describes Clarence as "a faithful preacher of the Gospel and a devoted and conscientious pastor". His wartime experience no doubt shaped his particular interest in conflict resolution, a task to which Clarence committed himself throughout his ministry. He also took a special interest in the congregation's youth, often spending his brief summer vacations as a leader at youth summer camps.

|

| Rev. Clarence William Cook in later life. |

Upon returning to Canada, Murray completed a Forestry program at the University of New Brunswick and was hired by Price Brothers Pulp and Paper, a large Quebec company. He married Alice Avery, a native of Hartland, NB, and the couple soon gave Clarence and Gladys their first grandchild, Jane, in 1948.

In November 1949, Murray and a co-worker were navigating Quebec's Chicoutimi River on a surveying expedition for Price Brothers. Tragically, their canoe overturned and both men drowned. Murray was laid to rest in Willowbank Cemetery, Wolfville, NS.

Clarence was also an active member of the communities in which he ministered. A member and Past Master of Markland Masonic Lodge, Kingston, NS, he was also a member of the Royal Canadian Legion, serving as Chaplain of its Habitant Branch at Canning, NS in his later years.

Clarence William Cook passed away at his Canning, NS hoe on July 13, 1961. He was laid to rest beside his son, Murray, in the Cook family plot, Willowbank Cemetery, Wolfville, NS.

*****

Sources:

Hogan, David B.. "The Eventful History of the Number 9 Stationary Hospital (St. GFrancis Xavier University), Canadian Army Medical Corps (1916 - 1920)". Annals of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, Volume 28, No. 6, September 1995.

Hunt, M. S.. "No. 9 Canadian Stationary Hospital." Nova Scotia's Part in the Great War. Halifax, NS: The Nova Scotia Veteran Publishing Co., 1920. Available online.

Raleigh, Walter & H. A. Jones. The War In the Air: Being the Story of the part played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force, Vol. IV. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1934. Available online.

Service Record of 2nd Lieutenant Clarence William Cook. Library & Archives Canada, Ottawa: RG 150, Accession 1992-93/166, Box 1939 - 32. Available online.

Special thanks to Clarence's great-nephew, Chris Cook of Linwood, NS, who graciously provided a copy of Clarence's Royal Flying Corps service file, pictures and information about his post-war life.