Place of Birth: Goldboro, NS

Mother's Name: Laura (Giffin) Ferguson

Father's Name: John Robert Ferguson

Date of Enlistment: October 5, 1915

Regimental Number: 91907

Rank: Gunner

Force: Canadian Expeditionary Force

Name of Unit: 1st Canadian Siege Battery

Location of service: France & Belgium

Occupation at Enlistment: Machinist

Marital Status at Enlistment: Single

Next of Kin: John Robert Ferguson, 87 Willow St., Halifax, NS

*****

Frank Byron Ferguson was born on January 4, 1890 in Goldboro, Guysborough County, where his father John worked as a blacksmith in a local gold mine. The family moved to Waverley, outside Halifax, several years after Frank's birth. John and his wife Laura later relocated to Dartmouth and finally north end Halifax, where they raised a household of five boys and one girl.

Frank started school at age seven, but left for the world of work at age twelve. His limited formal education, however, was not a hindrance in later years. Throughout his life, Frank maintained an intense curiosity about the world around him. Later diary entries are replete with literary and historical references, indicating that he was an avid reader with an outstanding memory. He also possessed a critical mind, complemented by an entertaining sense of humour.

|

| Gunner Frank Byron Ferguson |

Frank's travels, however, were far from over. The outbreak of war in Europe offered an opportunity to experience another part of the world. In 1915, Frank Ferguson returned to Halifax, where, on October 6, he enlisted in the 1st Canadian Siege Battery.

*****

The 1st Canadian Siege Battery was recruited largely from three Canadian cities - St. John, New Brunswick; Montreal, Quebec; and Coburg, Ontario. Renamed the No. 1 Canadian Siege Artillery in January 1917, the unit consisted of 6 officers and 210 "other ranks" at the time of its departure from Canada. The battery was eventually equipped with four 9.2 inch, British manufactured Howitzers and was first deployed on the Western Front in June 1916. Its members were part of the Canadian Siege Brigade, a force that consisted of thirteen siege batteries and two heavy batteries by war's end.

Throughout his military service, Frank kept a personal diary of anecdotes and observations on the war. Its content reveals much about Frank as a person. At times humorous, at other times reflective, the entries reveal the experience of war from the viewpoint of a "rank and file" artillery gunner.

Frank departed Halifax aboard the SS Saxonia on November 22, 1915, arriving in England on the last day of the month. The battery immediately began training for deployment at the front. Frank's December 20, 1915 diary entry reveals his blunt assessment of this experience, as well as his sense of humour: "Drilled on six inch howitzers this a.m…. So far I can't see anything noble or heroic about this man's war, because all I've done is march until my feet feel like kidneys, or slip and slide around a sloppy, wet field carrying a big iron drill shell that made me so humpbacked I must resemble the fellow who made Notre Dame famous."

Frank's diary entries present a cynical - at times openly critical - perspective on his commanding officers, whom he sarcastically called "the Brains". One diary entry states: "It would not surprise me a bit if they put us to work mounting one of the guns for drill purposes. And let it be known that [the fact] we are quite capable of mounting those damned guns in our sleep would not have the least bearing on the matter." Frank was equally critical of the irrelevance of training activities to actual battle conditions. On December 27, 1917, he commented: "Here we've been in this war for over eighteen months, been through all sorts of tight places, overcome all sorts of hardships, and I may add, have altogether been a very efficient outfit - and now we got to learn to salute. Hot damn!" These criticisms reflect the sentiments of many "rank and file" members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

The work expected of a gun crew was indeed physically demanding. 9.2 inch Howitzer shells weighed almost 136 kilograms (300 pounds), prompting Frank to comment: "It's a braw job lifting them out of the slimy mud onto the trucks. Thank God for a strong back and a weak mind." The task of building a gun position was equally demanding. Frank's September 5, 1916 diary entry states: "Worked all day making a new gun position next to the old one, as the gun had shifted so much it was useless. Raining like the devil again and the mud is terrible. In fact, every time I take off my boots I look to see if my toes are beginning to grow webbed like a duck."

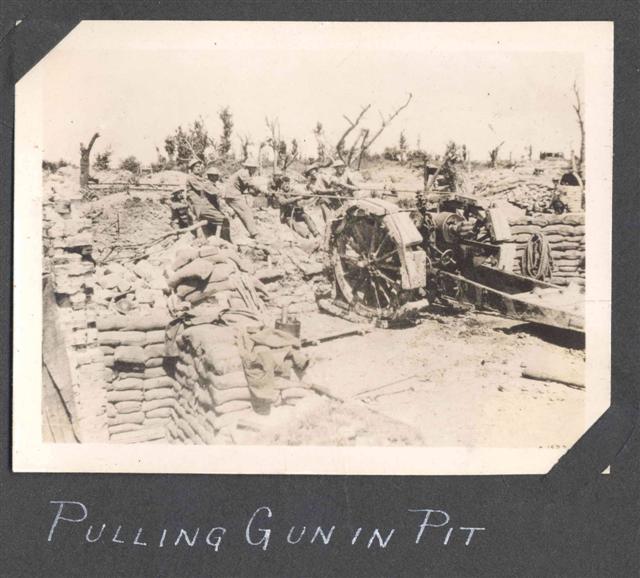

Relocating the battery's guns to a new position proved equally challenging. The first task was to remove the gun from its position, a task made more difficult by its tendency to sink deeper into the mud with use. According to Frank, "the whole outfit has to man the drag ropes. The caterpillars are useless here as they simply slip in the mud and cannot get traction." On one occasion, the crew required two days to remove the gun from its position. In another instance, "the ground was so soft that the guns sank up to the hubs in the mud and [the crew] had to build a corduroy road in order to get them out."

Setting up a new position proved equally challenging, particularly when the gun pit was located on the site of a previous battle. Frank's September 27, 1916 entry describes one such case: "At the new position today digging our gun pit…. This is a terrible place to try and set up a gun, as there are so many bodies everywhere and [we] must keep digging them out of the dirt where they have been since the [battle of] High Wood… in order to get the gun balks down. There are many hundreds all over this section, as this is where the South African Division was wiped out by machine guns… on 15 September."

|

| An artillery crew moving a gun into position. |

The physical demands placed upon the gun crew were second only to the risks to life and limb. As strategic military assets, artillery positions were under constant threat of enemy bombardment. On August 9, 1917, for example, Frank's gun position took a direct hit from a German shell, a fragment of which accidentally ignited shells stored behind the gun. To make matters worse, gun crews were changing shift as the shell struck. A total of 16 men were killed and another 12 wounded, 2 of whom subsequently died from their injuries. One gun was completely destroyed by the explosion. Its breech - weighing 300 pounds - was located a half mile from the gun position. A second gun, located thirty yards away, was put out of action by the explosion.

Shrapnel from exploding shells was another constant threat. On July 31, 1916, Frank described one tragic incident: "Poor old Kelly Lawton got hit in the head with a piece of shrapnel from a shell that landed by the 75 battery, and was killed instantly." On another occasion, a member of the gun crew was killed by "friendly fire": "A premature from one of the 60 pounders behind us came roaring over our heads. Scared stiff, I ducked down and saw the empty shell case strike the bank in front of the gun, just as poor old Stewart stepped out of his dugout. He didn't have a chance to duck…. He died as the gang carried him to the field dressing station."

Gas shells posed another hazard. Frank's September 6, 1917 entry described one such attack: "Last night we got another bad shelling with gas, but as we had put two gas blankets in the doorway and two more over the window, and then crawled into our bunks with our respirators on, we felt reasonably safe. We lay there trying to get some sleep, but the steady whee-plop of the gas shells soon put the idea out of our heads."

|

| 9.2 inch Howitzer shells (foreground). |

Artillery crew, like soldiers in front line trenches, also endured the inconvenience of rats in their living quarters. One diary entry describes a humorous encounter with the nasty pests: "It's too big a job writing here at night with the damn rats as big as kittens running all over the place. The other night Reid woke us all up out of a sleep sputtering and swearing. The grandfather of all the rats on the Western Front stepped in his mouth as he was snoring, and boy, what a commotion he made."

As a person with a natural interest in machines, Frank was fascinated by two of the war's new technologies - the tank and the airplane. Upon observing his first "land ship", as tanks were initially called, he commented: "My blinking oath, what queer things one sees in this war, and had I been a drinking man, I would have had good cause to sign the pledge after seeing the old buckets of bolts lumbering along the road, snorting and shooting fire from their nostrils like blooming dragons."

When his schedule permitted, Frank travelled to nearby aerodromes to watch the war's other major technological advance take to the skies. As a mechanic, he was not impressed with what he saw: "How the powers that be expect men to go over the line in the sort of crates these boys fly is a mystery. Some of them are already half shot away with holes patched with adhesive tape, and with motors that sound like a rest in a nice pile of junk would do them a lot of good."

|

| 9.2 Howitzer in action at Ypres 1917. |

*****

Frank's gun pit service followed the course of the war experienced by the majority of soldiers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. On July 1, 1916, his siege battery joined in the launching of the Somme offensive, a major Allied assault on the German front lines. The standard infantry attack began with an artillery barrage, which Frank described in these words: "Boy, talk about noise, the ground really shook with the shock of gunfire." Allied troops advanced so rapidly that the artillery guns were out of range by 10 am, leaving Frank free to wander down to a communication trench to watch the wounded and prisoners returning from the battle: "I fully expected the war to be over this afternoon so great is the number of wounded and prisoners coming in. All roads are choked with ambulance cases coming out, while the trench is filled to capacity with walking cases…. Thousands of healthy men shattered to the sacrifice of war."

One particular soldier, suffering from "shell shock", caught Frank's attention: "His face reminds me of one who has received a severe scare, wild, hurt, drool dropping from his mouth and running over his tunic, all the time, although speechless, an unceasing moan came from him…. It was about three days later that I saw the same chap on his way up the line with a bunch of reinforcements, and he looked entirely changed; but I don't think he will last long when the whizz-bangs start to land close to him."

On April 8, 1917 - Easter Sunday - Frank's siege battery prepared to support the Canadian Corps' assault on Vimy Ridge: "During the night 1420 shells arrived on lorries and all hands are busy washing them and putting them in nice neat rows. Had to roll them for a while. Then went to the guns to fire 500 rounds. A swell lot of Christians we are."

The following morning, the Corps launched its attack on the German positions. Frank recalls the beginning of the battle in these words: "Was awakened this morning before daylight by a terrific bombardment. What a sight in the dim light as the guns put down a barrage for the boys to go over the top and try for Vimy Ridge. What a terrible racket as all the guns on the front blended into one continuous roar and the flashes from them made the effect of a great electrical storm." Later in the day, he proudly noted that "the ridge was taken this morning, and according to the infantry they could have gone clear to Berlin if the artillery could have been brought up to cover them."

In October 1917, Frank's siege battery was relocated to Ypres, Belgium to assist in the Canadian Corps' assault on Passchendaele. He was not impressed with his new surroundings: "As far as I can see there is not much to be seen except a lot of old bricks and mortar, MUD, New Zealanders and more MUD…. A hole dug here will fill with water almost as it is dug…. It is raining to beat the band - the usual state of weather in the [Ypres] Salient." As terrible as the conditions were, they were overshadowed by the heavy price the Canadian Corps paid for its victory in the early days of November: "Since the arrival of this outfit in the Ypres Salient we have had so many killed that the army has given us a cemetery to bury them in, and it looks like the O. C. has been dared to fill it."

Frank enjoyed a second leave to London, England early in November 1917: "To be able to walk about without having to duck at every strange sound and to see the people at the Strand Corner House eating real meals has the effect of making one a confirmed pacifist from this time on." Frank took some time to visit a comrade's family and Madame Tussaud's famous museum, and enjoyed several of the popular shows and films of the day. He also took the opportunity to visit the dentist and "have a few teeth plugged…. I may outlive this damn war and then I will be sorry that I didn't look after the old molars."

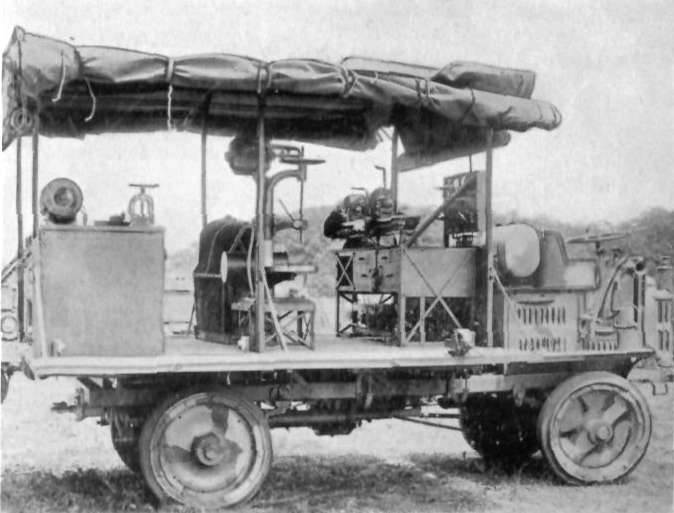

Despite his mechanical expertise, Frank spent his first six months in one of artillery battery's gun pits. Finally, in January 1917, his skills at repairing machinery were recognized and he was relocated to the battery's "tiffy shop", where he passed the days repairing gun parts and manufacturing whatever equipment the unit required. Frank happily recorded the event in his diary: "Yours truly is no longer a common gunner in this man's army, as the 'Brains' have at last decided that I am of more value to the army as a mechanic, and have removed my valuable person from the gun crew to the 'tiffy shop'…. There with forge and anvil and tools of every description, I feel more at home than loading shells into the yawning maw of a howitzer."

|

| World War I artillery repair truck. |

As the war drew to an end, Frank was amongst those fortunate enough never to have been wounded in action. His only hospital stay during the war was a case of influenza in January 1918, for which he spent ten days under the care of the 12th Canadian Field Ambulance.

After the signing of the Armistice on November 11, 1918, Frank remained in France until a case of tonsillitis led to his admission to 14th Canadian Field Ambulance on February 6, 1919. One week later, he was transferred to the 32nd Stationary Hospital at Wimereux, France. Upon examination, Frank was "invalided" as unfit for duty due to illness and transferred to England for recuperation. On February 19, he was admitted to the Graylingwell War Hospital, Chichester, where he spent one week convalescing before being transferred to the Princess Patricia Canadian Red Cross Hospital, Gooden Camp, Bexhill. Finally, on March 7, Frank was discharged as "fit for duty" and assigned to the CEF General Depot at Witley.

On April 12, Frank was transferred to CMDC Wing, Kimmel Park, in preparation for return to Canada. On May 3, he boarded HMT Royal George at Liverpool for the journey home. Gunner

Frank Byron Ferguson was officially discharged from military service at Halifax on May 18, 1919.

*****

After the war, Frank married Laura Rideout, a native of Twillingate, Newfoundland, and eventually returned to the United States with his young bride. For years, he owned and operated a repair garage in Brooklyn, New York, while Laura found work in the city as an accountant. Frank became an American citizen in 1929.

'Gunner' Ferguson never forgot his war experience. He kept in touch with his siege battery comrades and was active in organizing reunions. In 1936, he and Laura travelled to Europe to attend the official unveiling of the Vimy Memorial in northern France. Frank took the opportunity to revisit the locations where he had been stationed during the war.

In 1950, Frank retired from full-time work and returned with Laura to his birthplace in Goldboro. For many years, he drove to Houston, Texas each November, spending the winters working in a friend's machine shop until old age made the long journey impossible. Frank Ferguson died at his Goldboro home on September 10, 1975, the last surviving member of his immediate family. He was laid to rest in Bayview Cemetery, Goldboro.

*****

Sources:

1st Canadian Siege Battery. Guide to Sources Relating to Units of the Canadian Expeditionary Force: Artillery. Library and Archives Canada. Available online.

Regimental documents of Gunner Frank Byron Ferguson, No. 91907. Library and Archives Canada. RG 150, Accession 1992-93/166, Box 3044 - 47. Available online.

Rogers, Peter G., Editor. Gunner Ferguson's Diary - The Diary of Frank Byron Ferguson, 1st Canadian Siege Battery, Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1915-1918. Hantsport, NS: Lancelot Press, 1985.

It's nice to read about the life of someone who was in my family a long time ago.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the response. I'm pleased to read that you have a family connection to the story. The entire diary is a most interesting read, if you're able to locate a copy.

ReplyDelete