Both the Conservative Opposition and French Canadian nationalists opposed its creation for different reasons. Conservative leader Robert Borden advocated a direct financial contribution to the British Navy, while French Canadian nationalist Henri Bourassa argued that either choice would needlessly drag the country into future European wars.

Despite this opposition, the Laurier government proceeded with its plan, establishing the Naval College of Canada in Halifax to train officers for a small but permanent naval force. On February 1, 1911, recruiting posters seeking candidates appeared in post offices across the country. In addition, the government set about creating a 'naval reserve' available for service in time of emergency.

|

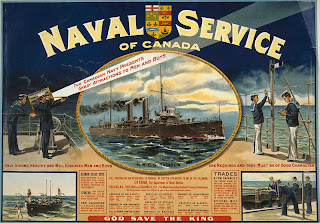

| Naval Service of Canada recruitment poster. |

The Laurier government's defeat in the September 21, 1911 federal election dramatically changed these plans. Canada's new Prime Minister, Robert Borden, had pledged to repeal the Naval Service Act. While he did not follow through on this promise, the Conservative government significantly reduced RCN funding, forcing it to tie up its two training vessels and abandon its ship construction plans. The creation of the Royal Naval Canadian Volunteer Reserve (RNCVR) on May 14, 1914 was the only significant development prior to the outbreak of war in Europe. Initially operating on a meager annual budget of $ 200,000 and consisting of only 1200 men, the RNCVR would play a major role in the impending conflict.

When war erupted in Europe, the RCN thus consisted of two ships - HMCS Rainbow stationed in Esquimault, BC and HMCS Niobe based in Halifax, NS - supported by a handful of officers and a tiny volunteer reserve. The British Imperial government recognized that Canada could not quickly construct a naval fleet sufficient to patrol its coastal waters and asked the Borden government to focus its efforts on recruiting infantry units. In the meantime, the Royal Navy officially assumed responsibility for protecting Allied shipping in Canadian waters and the North Atlantic Ocean. While regular and reserve officers and sailors immediately reported for duty in both the RCN and RN, throughout the war Canada struggled to raise sufficient naval manpower.

On Canada's Pacific shoreline, British, Japanese and Canadian naval vessels assumed responsibility for coastal defense. HMCS Rainbow, supported by a flotilla of auxiliary vessels, patrolled British Columbia coastal waters from the Strait of Juan de Fuca to Prince Rupert. The Rainbow later made three extended patrols in search of German naval vessels, sailing as far south as Panama. Smaller than its sister ship Niobe and thus more economical to operate, the Rainbow was nevertheless poorly equipped should it have engaged the enemy in combat and was officially 'retired' from service by the end of 1916.

At the beginning of the war, British Columbia's provincial government purchased two newly constructed submarines from a Seattle, Washington shipyard to aid in coastal defense. The vessels, originally intended for the Chilean Navy, joined the RCN's Pacific fleet and patrolled the province's coastal waters for three years. When anticipated German attacks in the region failed to materialize, the two submarines made the long voyage through the Panama Canal to Halifax, arriving in October 1917. Upon further inspection, they were deemed unfit for trans-Atlantic passage and spent the remainder of the war at a Halifax dock, where they were eventually sold for scrap in 1920.

Naval patrols of the Atlantic Ocean and coastal waters posed a much greater challenge for the fledgling RCN. At the time of the war's outbreak, HMCS Niobe sat dockside in Halifax. Having run aground in 1911, Niobe had undergone costly repairs before budget cutbacks temporarily halted further activity at sea. Its larger size necessitated a much larger crew and created significantly higher operation costs. Despite these obstacles, the Niobe was quickly reactivated after the outbreak of war, returning to sea in early September 1914. On its first assignment, the ship escorted a Canadian troopship from Halifax to Bermuda and back as it transported the Royal Canadian Regiment to its one-year garrison assignment on the small Caribbean island.

|

| HMCS Niobe |

The German submarine threat in the Atlantic created the RCN's greatest challenge. Throughout 1915, Germany focused its naval resources on British shipping in European waters. In the meantime, the RCN organized a fleet of auxiliary vessels responsible for Atlantic coastal anti-submarine patrols. While threat levels were moderate during the war's early years, by mid-1916 German U-boats reached Canadian coastal waters, launching attacks on Allied surface vessels in October 1916.

In response, the RCN announced plans to construct a fleet of ships modeled on wooden-hulled vessels serving in the Royal Navy at that time. Designed for minesweeping and coastal patrol duties, many were converted into fishing vessels after the war. In the interim, existing government vessels, private trawlers and even yachts were refitted and integrated into the RCN's anti-submarine fleet. For example, the Acadia, a government hydrographic vessel, was commissioned as a patrol vessel in 1917 and cruised the Atlantic coast for the duration of the war. Today, it rests in Halifax harbor as part of the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic's exhibits.

The story of the HMCS Grilse provides an example of a private vessel commissioned for naval service. Originally built as the private yacht Winchester, the ship was purchased by Montreal millionaire industrialist Jack Ross in June 1915 and refitted at Vickers Shipyard, Montreal. Converted into a torpedo boat, Winchester was commissioned HMCS Grilse in July 1915. Capable of speeds in excess of 30 knots (55 km/h), it became the RCN's fastest vessel and served off Canada's Atlantic coast under Ross's command for the duration of the war.

On February 1, 1917, Germany publicly announced its intention to launch a campaign of "unrestricted submarine warfare" in Atlantic waters. After the United States' entry into the war on April 1, 1917, its naval vessels supported British and Canadian ships in response to the growing U-boat menace. By this time, Britain's imperial anti-submarine Atlantic fleet consisted of 50 vessels. As the threat of attack worsened, its size increased, reaching 116 vessels - a total of 29 RCN and 87 RN ships - by war's end.

During the summer of 1917, the British and American navies implemented a convoy system for escorting troop and supply ships across the North Atlantic. The first escorted convoy left Halifax Harbour on July 10, 1917, with subsequent convoys sailing for Europe and the Mediterranean from Sydney, New York and Hampton, Va. throughout the remaining months of the war.

|

| HMCS Rainbow |

Second, the Royal Naval Canadian Volunteer Reserve had expanded from a meager 350 to over 5000 men by 1918, providing a trained pool of skilled sailors and officers from which the RCN could draw in time of crisis. While the RNCVR was officially disbanded on June 15, 1920, it was replaced by the Royal Canadian Naval Reserve three years later. When war once again erupted in Europe in 1939, this pool of skilled sailors and officers provided a critical resource during the Battle of the North Atlantic.

In addition, the Canadian government began construction of a small fleet of modern vessels specifically designed for naval service. The first, HMCS Shearwater, was commissioned in 1915 and served throughout the war. While decommissioned in 1919, the Canadian government continued to build naval ships over the next two decades. By 1939, the RCN consisted of 11 combat vessels, 145 officers and 1674 sailors - a notable increase when compared to its meager 1914 resources. Overall, the RCN's experiences during World War I created both the political will, physical and human resources required for the development of today's Canadian Navy.

*****

Sources:Canada's Naval History: Birth of the Navy. Canadian War Museum. Available online.

Canadian Naval Operations in World War I (1914-18). H.M.C.S. Sackville: Canada's Naval Memorial. Available online.

History Spotlight: 100 Years for Canada's Navy. Canada's History. Available online.

The Naval Service of Canada Before World War One. Canada At War. Available online.

Royal Canadian Navy. Wikipedia: The Online Encyclopedia. Available online.

No comments:

Post a Comment